OUR TEN FAVORITE POSTS

Today marks our 1,000th post on Instagram. To celebrate we are looking back at ten of our favorite NYC Urbanism posts over the last two years! (March, 15, 2018)

1. JOSHUA BEAL'S 1873 BROOKLYN BRIDGE PANORAMA

Joshua Beal, 1873. Click to enlarge.

On a cold January morning in 1873, photographer Joshua Beal wrestled his heavy camera equipment including a tripod and glass plate negatives up thirty stories to the top of the newly topped-out Brooklyn tower of the Brooklyn Bridge. Overlooking Lower Manhattan, Beal photographed five glass plate negatives, which combined, form a sweeping panorama of the city measuring 9 x 89 inches!

The panorama, which runs from the Battery to Pike Slip shows a drastically different Manhattan skyline than the one that would emerge within the next 20 years. As seen in the panorama, most buildings reach no more than five stories, and the overall landscape is low save for a few high buildings in the background. These were churches and the first skyscrapers—the Tribune and Western Union Buildings, offering a glimpse of what was to come. The tall, slender, tower seen to the left of the massive City Hall Post Office is the 175-foot McCullough Shot Tower, which produced round bullets by dropping molten lead from a great height. Also striking is the commercial activity along the East River, with docks and slips at the end of every street and hundreds of tall ship masts dotting the skyline. The under-construction Manhattan tower of the Brooklyn Bridge, seen towering over the city would top out shortly after the photo was taken. The bridge would open seven years later.

2. SUGAR HOUSE PRISON WINDOW

Sugar House Prison Window. NYC Urbanism, 2016.

Behind the Manhattan Municipal Building next to the Brooklyn Bridge and One Police Plaza is an old Revolutionary War prison window dating back form 1763. During the Revolutionary War sugar houses were often turned into prisons by the British, with deplorable conditions. The window is said to be a vestige of the notorious Rhinelander (originally Cuyler) Sugar House prison used during the British occupation of New York between 1776 and 1783 where hundreds of American POWs died of starvation and disease.

The New York Correction History Society describes the use of New York City Sugar Houses as Prisons during the war:

"One of the least known and least spoken about subjects of the Americans Revolution were rebel Prisoners of War who were jailed in New York City. . . . [The] City had become the main site for the prisoners because it was the only city to be held by the British for the duration of the war. Many of the prisoners were from the Battle of Long Island on August 26, 1776 (1,300) and from the Battle of Fort Washington on November 16, 1776 (3,000)."

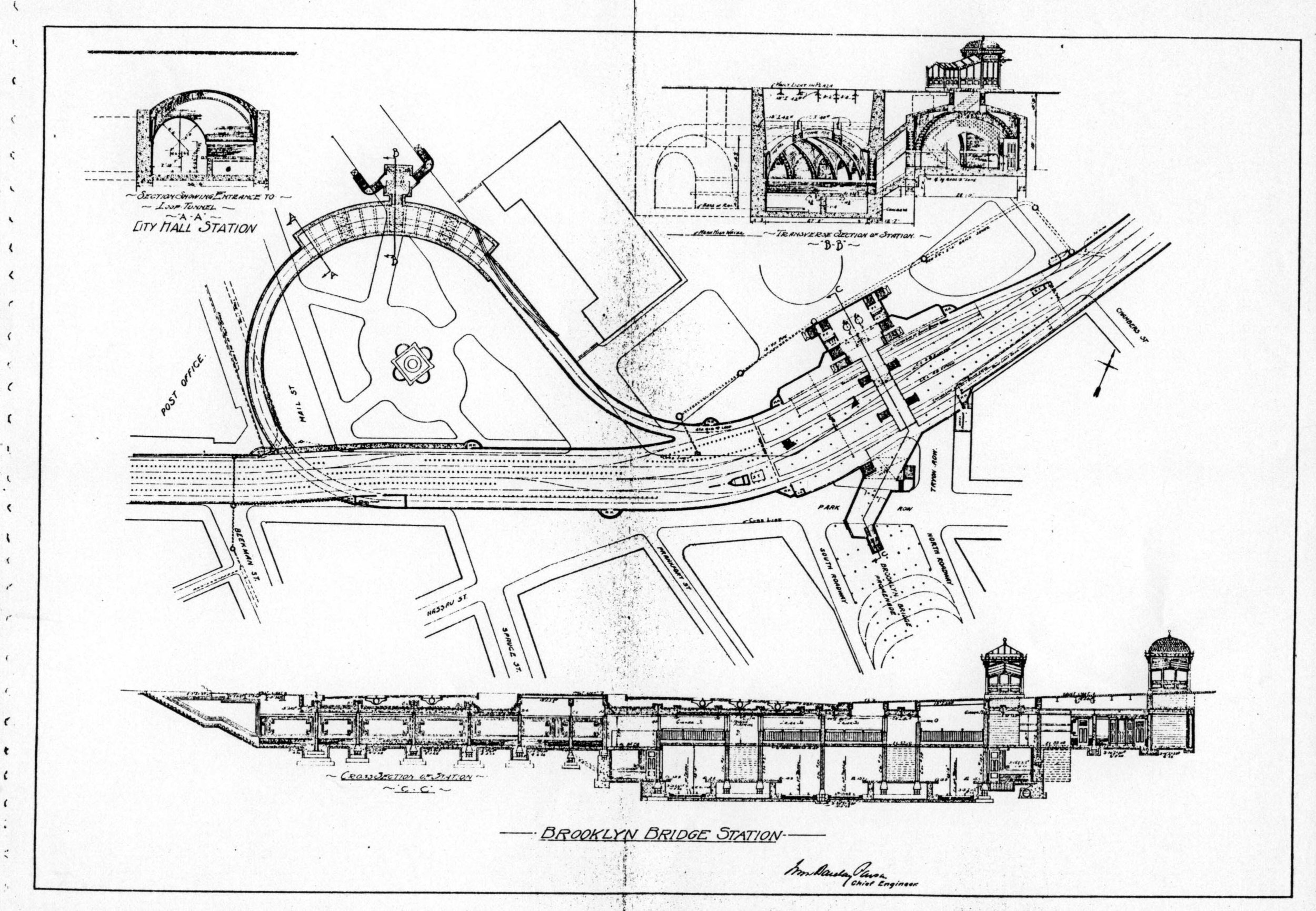

3. ORIGINAL CITY HALL SUBWAY STATION

Thanks to the Transit Museum we had the pleasure of touring the incredible old City Hall subway station. In 1904 the city's first subway line opened, with the City Hall station as the crown jewel of the system – the first station built and the site of the opening ceremony where the first train departed. The station featured skylights, Guastavino tiling, colored glass, vaulted ceilings, brass chandeliers and plaques commemorating the opening. Unlike the other 1904 stations, City Hall was built on a curve (seen above) and could only accommodate five-car trains. As the system expanded with larger trains, the station was eventually closed down in 1945. The Transit Museum and MTA restored the station during the system's centennial and there was even talk about making it an extension of the museum, but the station is directly under City Hall and therefore a security risk if opened to the public. Today the 6 train still uses the City Hall loop to turn around (see map above) and riders who remain on the southbound train after the Brooklyn Bridge – City Hall (final stop) can get a peak of the old station through the windows as the train passes. The station's chandeliers are rarely lit up, so check it out on a sunny day when the light is coming through the skylight.

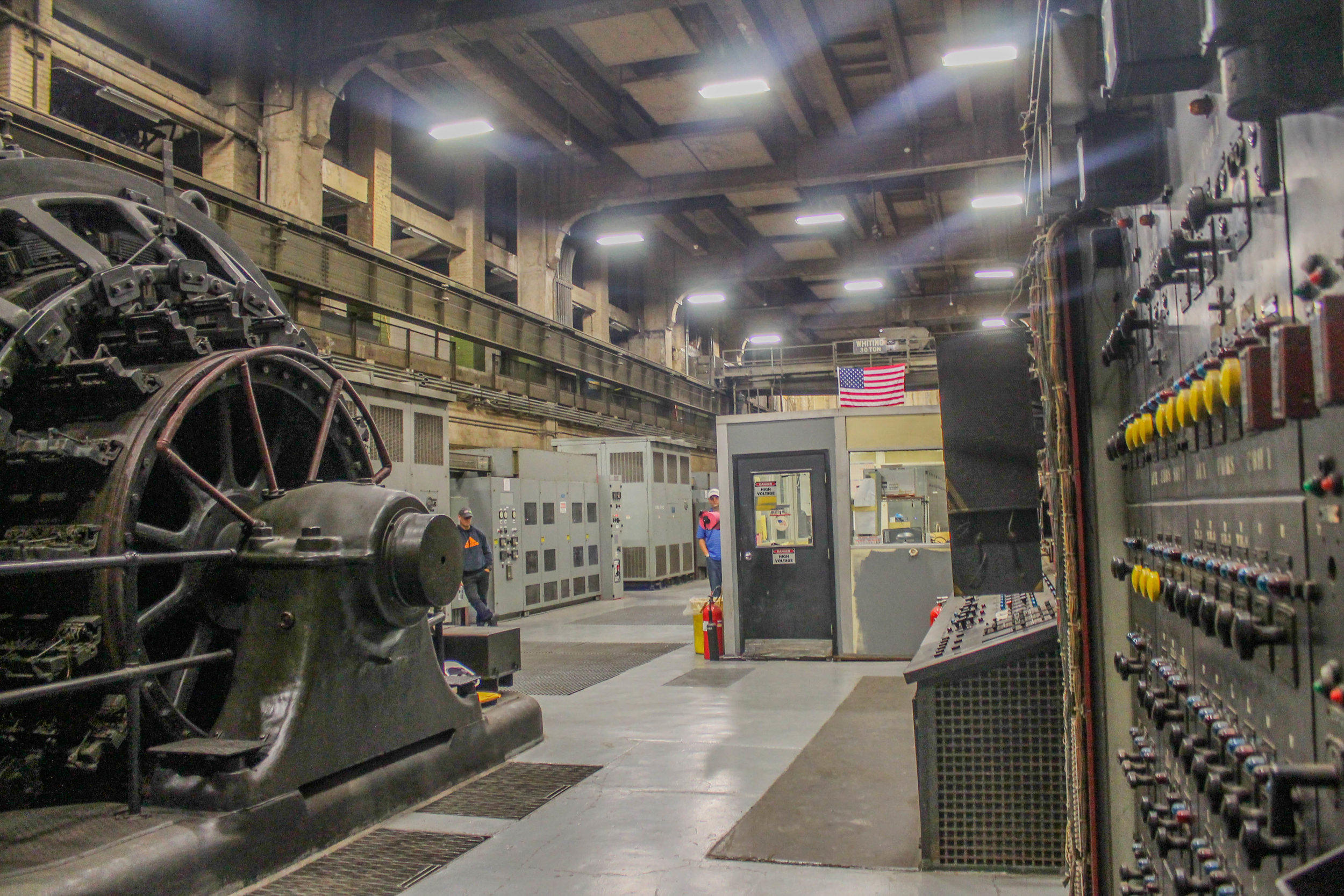

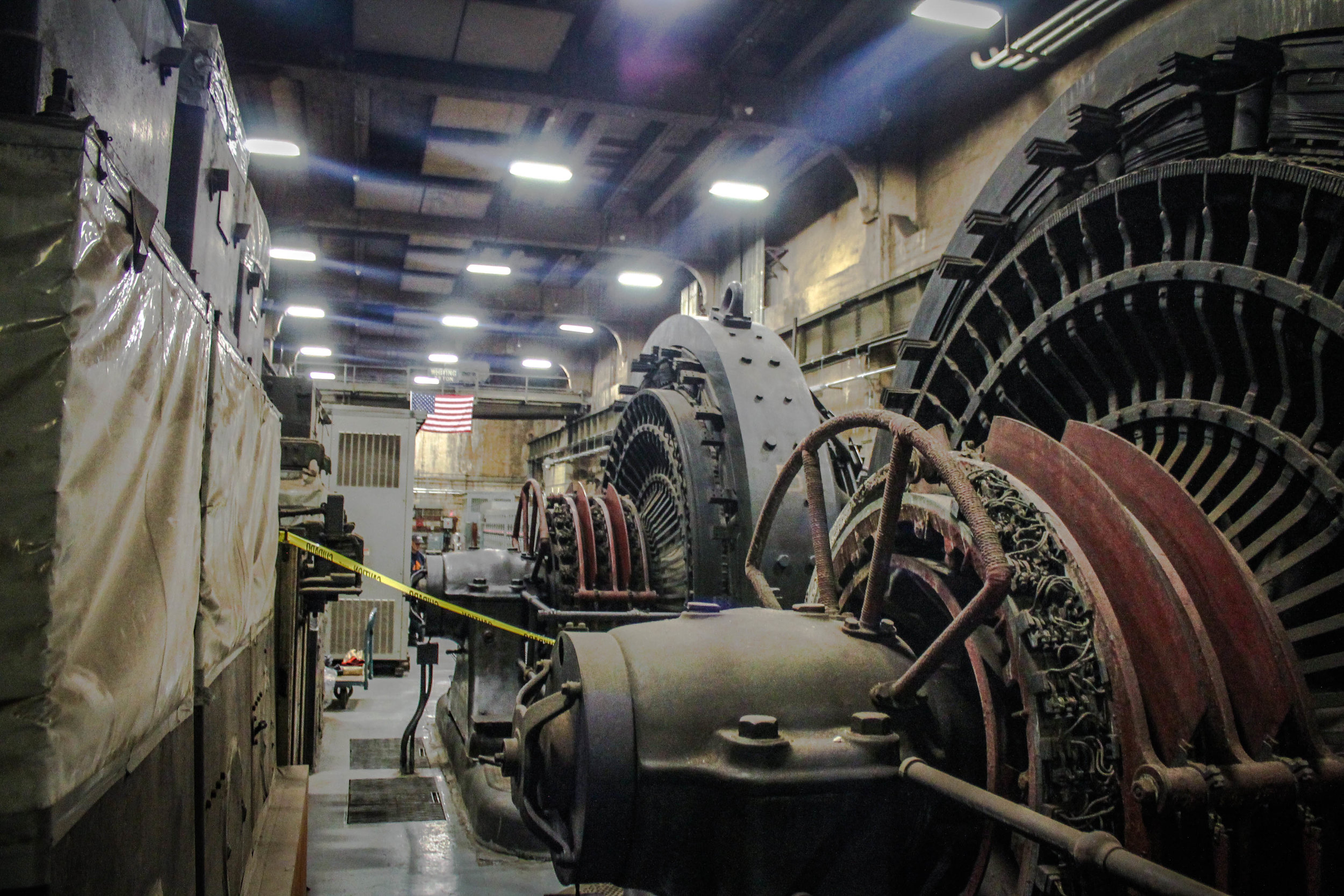

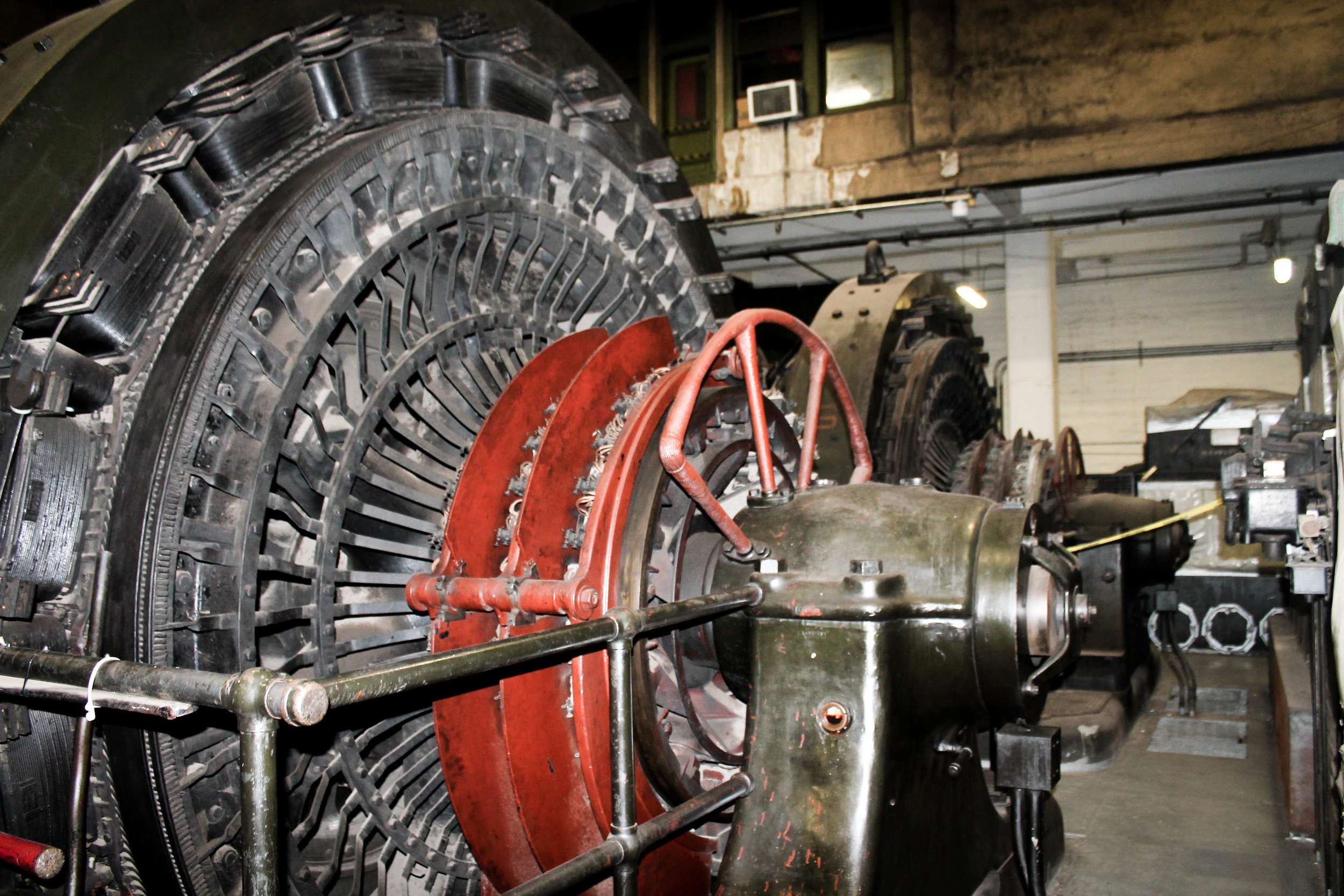

4. M42 - GRAND CENTRAL’S TOP-SECRET BASEMENT

The clandestine substation thirteen levels under Grand Central Terminal is off limits to the public and not listed on any blueprints or maps of the Terminal. Grand Central’s best-kept secret; its very existence was only acknowledged in the late 1980s.

Known as M42, the substation is supposedly the lowest elevation of any room in the city, only accessible by a long staircase that travels through layers of Manhattan schist bedrock or an old Otis elevator. When it was built in 1930 it was largest substation in the world, equal in size to the main concourse above. The 22,000 square foot room held nine rotary converters, converting 11,000 volts of AC to DC electricity to power the third-rail on 2,000 miles of track. In the late 80s the converters were replaced by modern 3,300-kW solid-state traction rectifier units, however, two of the original converters are still located in the substation, relics of the terminal’s historic past.

M42 played an important role in World War II. During the war, the room was so secret that armed guards were stationed at the entrance with orders to shoot anyone on site who tried to enter without proper clearance. But someone who worked in the room notified Hitler of M42's contents. Nazi spies targeted the substation, devising a scheme to halt the movement of 80% of the equipment and troops in the Northeast who used the rail network to transport around the region. The plan was to sabotage the substation, shutting off power to all the trains by dumping sand into the rotary converters, causing them to short circuit. The Nazis sent U-boats to the coast of Long Island in 1944, landing in the middle of the night. The spies were spotted by the Coast Guard who warned authorities before losing them in the fog. But the FBI was on high alert for the Nazi spies, who made one fatal mistake. When they arrived at Grand Central Terminal they checked their luggage, and the FBI was searching all the checked luggage. When the spies returned later that day to retrieve their bags, they were arrested and two were eventually executed.

5. JOHN RANDEL’S SURVEYING BOLTS IN CENTRAL PARK

One of Randel's bolts in Central Park

John Randel's Commisioner's Plan of 1811 Map

This surveying bolt was placed in Central Park by John Randel Jr., or one of his staff, who at the request of the NYC Commissioners in 1811 spent over a decade measuring and placing markers, usually marble monuments or iron bolts on every corner of twelve avenues and 155 blocks, more than fifteen hundred planned intersections that would become the Manhattan street grid. Central Park was not planned yet, so the corners of Sixth and Seventh Avenues between 59th and 110th Streets were surveyed. Traveling through swamps, forests, hills, and rivers Randel was able to map out the entire grid, corner by corner with immense precision, making it possible for Manhattan's to expand northward. He was often chased by property owners or wild animals. In 1818 Randel started creating a detailed map of the grid with the support of the NYC Council. The final product consisted of 92 maps, over 50 feet in total, the most detailed map ever created at the time. The map is held today in the Manhattan Borough President's office in the Municipal Building and shows the corners Randel surveyed that would become part of Central Park.

6. 70 PINE STREET'S MINI MODEL OF ITSELF

Left: 70 Pine's scale model of the skyscraper above the entrance. Right: 70 Pine aerial view.

One of the greatest Art Deco skyscrapers in NYC has a scale model of itself above its entrances. The 12-foot version of 70 Pine (formerly the Cities Services, then American International Building) is carved in stone on the north and south facades. Below the stone model is an even tinier version of the skyscraper; a scale model of the model!

The Cities Services/ AIG Building at 70 Pine Street was constructed in 1932 for Cities Services, a petroleum company who built the tower to house its corporate headquarters as well as rental floors. The company’s founder and chairman, Henry L. Doherty, an eccentric engineer and inventor who supervised the design of the tower and intended to live in the penthouse, although poor health prevented him from ever doing so. The top story was instead used as an observatory open to the public, originally furnished with chairs and other articles of furniture designed by Le Corbusier and Marcel Breuer. During a recent residential conversion, the penthouse was finally realized.

The skyscraper was originally known as 60 Wall Street, a more prestigious address that was justified by the tower’s connection by a footbridge (and an underground walkway) to a building with that address, now demolished. The 67 story tower rises as a slender shaft that is articulated with a series of shallow receding planes and at the top steps back to create a glass observatory which is illuminated at night. The brick cladding lightens from a browny-beige to a creamy-tan as the tower ascends. The base of the building is clad in a luxurious polished pink and black Minnesota granite. 70 Pine was the last high-rise to go up before the Depression hit, and consequently, the last to be erected before WWII.

7. HESS TRIANGLE - MANHATTAN’S SMALLEST PIECE OF REAL ESTATE

On a corner in the West Village is New York City’s smallest piece of private land. The tiled mosaic in front of Village Cigars on 7th Avenue and Christopher Street reads "Property of the Hess Estate which has never been dedicated for public purposes.” The land was once part of the estate of David Hess who owned a building on the site until the city demolished it under eminent domain in the early 1900’s to widen 7th Ave and expand the IRT subway. When the city seized the land they missed a small corner and the bitter Hess Estate set up a notice of possession, refusing to give the tiny triangle to the public. The current Mosaic was installed in 1922 and 10 years later sold to the Village Cigars store for $1,000. At the moment the plaque is still in place.

8. ELEVATED ACRE

Elevated Acre at 55 Water Street

This secret elevated public plaza at 55 Water Street was built in 1972. The building is the largest in floor area in the city and was built on a superblock by combining four city blocks along the waterfront between Front and Water Streets. The 1961 zoning law provided incentives to developers who provided public spaces on or around their buildings. Even though it is elevated and tucked away from the sidewalk, the one-acre public plaza at 55 Water allowed the developer to increase the total square footage. You can visit the plaza by taking the escalator in the middle of the building off Water Street.

9. FAKE BROWNSTONE IN BROOKLYN HEIGHTS

Fake Brooklyn Heights brownstone (middle) with blacked out windows. NYC Urbanism, 2015.

This Brooklyn Heights brownstone at 58 Joralemon Street in Brooklyn Heights is actually a decoy. The blacked out windowless facade is a ventilation shaft for the 4/5 subway East River tunnel that connects the Brooklyn Borough Hall station with Bowling Green in Manhattan. The first New York City underwater subway tunnel, the second subway contract from 1902 extended the original Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) subway line to Brooklyn via the Battery-Joralemon Tunnel, then up Fulton Street to Flatbush to the Long Island Railroad Terminal on Atlantic. Ground was broken in 1903 and the tunnel opened on November 27, 1907. The tunnel was comprised of two cast-iron tubes, 16 feet in diameter. When the tunnel first opened telephones were placed every 300 feet, monitored by an IRT employee in an office at Bowling Green who could watch the location of the trains in the tunnel via colored lights on a transparency. The tunnel runs under Joralemon Street in Brooklyn Heights, a cobblestone treelined block with postwar brownstones dating back to the late 1840s. To fit in with the surrounding neighborhood the IRT purchased the Greek Revival brownstone at 58 Joralemon and gutted it to place the ventilation shaft and exit inside the building's brick frame. Today hundreds of people pass the building every day without noticing the decoy.

10. 20 EXCHANGE

Left: 20 Exchange's Giants of Finance. Right: 20 Exchange Place.

In 1929, the City Bank Farmers Trust Company chose renowned architects Cross & Cross to design a new skyscraper that would solidify the banking institution's presence on Wall Street. The new building became one of lower Manhattan's most iconic skyscrapers, known for its ornate design and towering height. That year Cross & Cross unveiled a proposal for the tallest building in the world: a 71-story, 846-foot tower topped with an illuminated globe fifteen feet in diameter supported by four massive eagles. However, following the New York Stock Market the Bank was forced to reduce the height to 741.

Once construction began the skyscraper rose at a record pace and was completed in February 1931, less than a year later. One unique aspect of the design was the architect's insistence on high-end materials. The facade is clad in fine stones including Granite and Limestone. Inside, the architects used forty-five varieties of marble to adorn the spaces.

The exorbitant base features an array of sculptures, reliefs, seals, plaques, and medallions both inside and out. Eleven granite coins surrounding the arched entrance depict cities where the bank had branches. On the nineteenth floor at the first major setback, 14 massive heads known as "The Giants of Finance" look down on the street below.

When it opened in 1931, the skyscraper housed the largest pneumatic tube system in the world, the largest telephone exchange, and reservoirs in the basement that pumped hand soap to all the bathrooms.

The building has two separate grand banking halls, both of which are vacant today, largely used for movie shoots including Inside Man and the original Wall Street.

In 1955 the bank relocated its headquarters to Midtown and in 1976 the First National City Bank of New York was officially renamed Citibank. In the late nineties, the building was landmarked, completely restored and converted into residential units. Today, the building houses 767 units with amazing views of the city and amenities including an outdoor terrace overlooking the Giants of Finance.

Click here to read the full illustrated post on 20 Exchange.